or … How can we help students become independent of teachers?

(First published in ‘Singing’ – the Journal of The Association of Teachers of Singing (UK), Spring 2011)

What exactly is a warm-up, and who should be in charge?

Students often ask for ‘warm-up tips’ or what might be called a ‘recipe’ for warming up. They also often expect the teacher to warm them up at the start of a lesson. No singer has ever asked me what a warm-up is supposed to achieve. Clearly, a singer wants to make a good sound, over a wide pitch range, singing fast or slow, over vowel changes and when introducing consonants and words, over short and wide intervals, singing loudly or softly; they want everything to be healthy and feel as easy as possible, and they want good vocal stamina; and they want their voice to be a versatile expressive resource. The problem is, a singer can’t hear their own voice properly, which means that they cannot use the sound of their voices as a guide to how well they have warmed up. So how should they monitor themselves? How will they know when they are properly warmed up? And how can we ensure students don’t learn dependency on their teachers for getting them into perfect voice?

What teachers have to rely on

When teachers, coaches or choral directors help a student vocalist warm up (and work their voice e.g. on repertoire) they use their eyes and ears to monitor them: eyes, because they are used to watching for postural behaviour and subtle muscular activity that may help or hinder the singer; and ears, because, with experience and practice, it is possible to work out from details in the sound itself a lot about how that particular sound is being made. It is interesting how often a teacher can identify correctly when a singer has lost mental focus for a moment, or even what the singer thought – sound and muscle/body language are very revealing! To assess whether a singer is warming up successfully, teachers often ask the student to sing, and use their eyes and ears with a student because they do not have direct access to the thoughts and emotions that are influencing the singer’s body and voice, nor can they experience the proprioceptive feedback the singer receives from internal organs and nerve endings when stretching, moving, aligning, balancing, breathing, and vocalising. But, as should become clear in the course of this article, from the singer’s point of view, singing is in fact not the best way of starting a warm-up.

It can’t all be done with mirrors

Using a mirror can be helpful for a singer, especially if there is no one present who can give feedback. A singer can watch for postural issues and unwanted muscular behaviours. For a singer with little self awareness, using a mirror can be a small step towards addressing this.

However, while a singer can watch themselves in a mirror when practising, often they can still miss crucial visual feedback. For example, singers often don’t notice a twitch in their neck, shoulder movement, jaw tension, and so on. Even when an observer points out a muscular event, the singer watching the mirror will sometimes deny the event took place; singers sometimes notice much more watching playback of a video of themselves. In addition, facing a mirror, singers often do not notice the forward projection of their head or chin, the shoulder blades closed at the back, the shoulders pulled back behind the hip line, the excessive inward curve at the base of their spine, their locked knees, their tight jaw, and so on.

And in performance, there is no mirror anyway. Even if a singer becomes good at monitoring with a mirror, this does not help in performance; singers need to be properly prepared for the performance experience by replicating the conditions in practice time (ie singing without a mirror).

Should singers just learn to listen better?

Listening to one’s own voice as a singer is bound to distort healthy voice production. Adrian Fourcin has explained why in an excellent chapter called ‘Hearing and Singing’ in Janice Chapman’s 2006 book, Singing and Teaching Singing: A Holistic Approach to Classical Voice.

First, sound is directional, which means that the sound is less intense around the singer’s ears than it is for a listener (or recording equipment) in front of the singer. Also, the pattern of vibrations is complicated by interactions of sound waves around the head. Typically, the singer hears less, but wants to hear their own voice as loudly as they hear the singers around them (eg in a choir), or as loudly as they hear their voice on a recording, or they want to replicate the same intensity as the teacher’s vocal demonstration. Singers who want to hear their voice as ‘powerful’, or to match the volume of other voices or recordings, ‘force’ their voice, rather than ‘releasing’ it.

Second, a singer hears the vibrations of their own voice conducted through bone, tissue and fluid in the head. This affects the perception of volume; much is heard through body conduction, rather than through the air conduction in the room. This also effects perception of timbre (tonal quality); the lower harmonics sound stronger than the higher ones, as though the ‘bass’ is turned up or the ‘treble’ turned down on a hi-fi; so our voice will always sound less ringing or clear to us than to a listener. A singer producing a ‘thin’ tone voice, or who favours a ‘twangy’ tone may be listening to themselves, and trying to make their own voice sound ‘ringing’ or clearer to themselves; this will inevitably mean a tighter tongue and higher larynx position, which compromise vocal efficiency.

Third, the acoustic environment affects how the singer hears their own voice. Reflector surfaces vary from one space to the next, so there is no consistency in how the singer will hear the sound coming back, and different harmonic bandwidths (e.g. ‘treble’ or ‘bass’) can be enhanced or dampened. For example, it can be very disconcerting after practising in an empty hall before a concert to feel the sound being sucked away when the curtains are drawn and there are lots of audience bodies absorbing the sound waves rather than bouncing them back to the singer in the concert itself. An audience may hear a really good sound while the singer thinks their voice lacks power or colour. Typically, singers who try to make their voice sound ‘right or ‘good’ have weak body awareness, and do not trust their bodies; learning physical technique can be slow because the singer keeps listening and evaluating their sound rather than focussing on the physical skills that would actually improve the sound.

So, because a) much of the initial sound signal of the voice moves away from the singer or is distorted near the ears, b) much of what the singer hears is distorted by conduction of vibrations through the singer’s body, and c) acoustic environment influences the sound waves unpredictably, a singer can never know what they truly sound like to the listener, and should never listen to themselves when warming up, practising or performing.

Only well trained singers know how to translate information about sound back into what they need to do physically to modify the sound or make the process of singing easier. It is therefore often counter-productive if a teacher draws the singer’s attention to tonal quality or volume – they would do far better to give guidance on physical technique that would produce the desired sound.

How can a singer warm up their voice without listening?

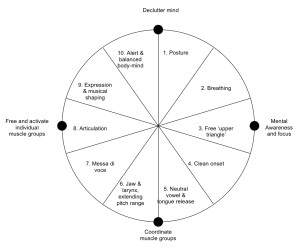

While singers might want to use their ears to decide how well they are doing, this is a very inaccurate and misleading method of self-evaluation. A singer needs to learn to trust other types of sensory feedback instead. Here is a model for how that might be achieved, framed as 4 aims, and 10 objectives:

The 4 AIMS for a warm-up (two physical, two mental):

- Free up and activate individual muscle groups – Even without vocalising, we can do a lot of stretching, bending, breathing, releasing of different muscle groups to prepare them for the act of making sound. The voice will always deliver better when the body is happy, and focusing on body first helps us get away from the temptation to listen to ourselves.

- Coordinate muscle groups – Again, a lot can be prepared without making sounds. For example, we can ‘ease the knees’, improve postural behaviour, lengthen the neck, and activate abdominals with an exhaled breath through pursed lips, without activating vocal folds. This prepares us for the correct ‘feel’ of the body and coordinated muscle groups, without being distracted by hearing our own voice. The vocal folds can only be exercised fully by actual sound-making, so this needs to be introduced in due course in the warm-up process.

- Develop awareness of and mental focus on 1 and 2 – Singers need to know their body, because it’s the body that makes the vocal sound. A warm-up should aim to heighten the singer’s awareness of what the different muscle groups are doing, and how they are interacting in the act of making vocal sounds. Awareness brings mastery, bearing in mind that there can be a point ‘beyond awareness’ where everything is in ‘flow’ and we are just ‘in the zone’. But the independent singer (one who does not need to rely on a listener’s or teacher’s feedback or coaching) must enhance ever greater levels of self- and body-awareness.

- Declutter the mind – As well as making sure we have detached from wanting to monitor our own sound quality, we also need to let go of attending to extraneous thoughts, whether it is audience responses or needs, the washing up, whether we will make a mistake and lose face or not, or a stray noise or movement in our environment. Unless we can do this, we have little chance of doing 1, 2 and 3 well.

Singers can judge for themselves how well they are meeting these four aims, and none of them depends on listening to oneself.

10 OBJECTIVES for navigating and assessing a warm-up:

- Before making sound … Are the knees loose (‘ease in the knees’)? Is the lower back relatively flat? Do the middle and upper back and shoulder blades feel open? Are the shoulders sitting above the hip and feeling loose? Is the back of the neck long? Does the body feel ‘fluid’?

- Do pelvis, belly and abdominal muscles (rather than middle, upper chest and ribs) feel like they are doing most of the work in ‘breathing for singing’, while the ribs and back feel wide? (I call the abdominal-pelvic muscle system the downward-pointing ‘lower triangle’.)

- Do the shoulders, neck, tongue, jaw and lips feel free and loose?

- Adding sound … Does the onset (beginning) of a note on a vowel feel ‘clean’, started by a neat coordination of breath and vocal fold vibration, rather than a sharp glottal click or ‘attack’ in the throat (are we singing through the throat, rather than with the throat)?

- When vocalising on a neutral vowel, do the shoulders, neck, throat, tongue, jaw, and lips (ie everything from shoulders upwards, what I call the upward-pointing ‘upper triangle’) feel like they are ‘doing nothing’? NB While there may be subtle muscle adjustments in the mouth for resonance, not least to accommodate different pitch areas, the subjective ‘feel’ should be as if there is virtually no activity in the ‘upper triangle’.

- Do the muscles around the back of the jaw and underneath it feel free? And does the larynx feel low (without being ‘forced’ downwards)? Even when exhaling? Even when vocalising? Over a wide pitch range, scales and arpeggios? Over slow and fast passages?

- Is this still the case when doing slow note practice on crescendo and diminuendo (getting louder and softer on single notes or phrases as in a messa di voce exercise)?

- Adding articulation … When adding vowel changes, and, later, consonants and full words, does it still feel like the ‘lower triangle’ is basically running the voice? Is there very little sensation in the throat / neck muscles, jaw, tongue, soft palate and facial muscles because they are working with minimal effort?

- Connecting with the ‘inner life’ of singing … Does the body (breath mechanism, throat, mouth resonators and articulators) feel responsive to be able to express subtle changes of emotion, and the various demands of genre, drama, and musical shaping?

- Does everything feel alert, but easy, and does the mind feel calm and aware, rather than ‘revved up’, narrowly focussed on sound, one muscle group, or something extraneous? This question may seem too ‘touchy-feely’, but we need to ask ‘is what we are doing everything it can be?’ (given our circumstances on the day). And we must answer with intuition, with whole self and ‘felt sense’. ‘Thinking’ too hard narrows our awareness and takes it away from a comprehensive body-mind consciousness.

(Click on the image to see a large view, and click the back button to come back to this article.)

It is understandable that a singer might want feedback on the sound they create during their practice time, or in a performance. Since listening to oneself during the act of singing is counter-productive, monitoring sound is best achieved by listening back afterwards to an audio or video recording. The advantage of video is that it can also provide at least some information on what the singer was doing physically when singing or performing. But of course, we must remember the limitations of recording technology – a microphone only captures some elements of the singer’s sound, so the playback is not an exact reproduction of what a listener would have heard.

Good teachers and conductors ‘hand singers back to themselves’ (see ‘Who’s in charge of a student’s learning?‘)

A good teacher or reliable singing colleague can help singers achieve all of these things. But if they are doing the monitoring and advising for the singer, then the singer does not learn to trust themselves, and their own proprioceptive feedback as singers. So from the very earliest stages of learning, teachers/choral directors need to help students develop these self-monitoring skills – otherwise students and teachers unconsciously collude in the student developing a dependency on the teacher, and diminished self-trust for both practice and performance. A teacher is failing a student who says they always sing better in a lesson than anywhere else. Good teachers ‘hand singers back to themselves’, and help them to become independent learners, and able to trust themselves in private practice and warm-up time as well as in the performance space.

What do students need from teachers?

Every teacher has ideas about how to help students warm up. It is not unusual to encourage singing within the first few minutes of a lesson. The teacher then responds with guidance on the basis of what they see and hear. However, this does not model what the student needs to do when alone. The unconscious message singer-students receive is that phonating, watching and listening are the primary means by which they should warm up, and how they should monitor their own warm-up – this is not good. Even if the teacher encourages physical releases first, the teacher still proceeds to giving feedback when they hear the student’s first sounds – so sound, and the teacher’s feedback, remain the primary focus.

Teachers need to consider how to teach students how to warm themselves up and monitor themselves appropriately. This means that, at least sometimes, teachers should not ask a student to sing straight away, but ask them to demonstrate, in real time, their warm-up process, talking the teacher through how they make their decisions each step of the way. This can prove extremely illuminating, for both student and teacher! The teacher can offer useful prompts. For example, the question ‘what are you noticing?’ might receive an answer from the student about the sound (ie they’re listening), or that they lost confidence as they rose in pitch (ie they mentally distracted themselves from monitoring their body, and perhaps were anxious about how good their sound would be).

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

(George Box, statistician, b. 1919)

Rather than monitoring students on their behalf, teachers need to train students in self-monitoring, and show them how to work out what is needed for their voice. Students need teachers to give not just warm-up exercises, but a philosophy and decision model for warming up. This article sets out:

- a rationale for what a warm up should achieve, and how to judge its success

- criteria for evaluating, choosing and discarding different warm-up methods

- a map for navigating a warm-up session (as well as trouble-shooting in a practice session, singing lesson, or performance)

- a means for a singer to unhook from dependency on mirrors, feedback from observers, or listening to themselves

No article or system can cover everything, fit every reader’s way of thinking, or address every possible question or objection. While physiological principles are universal, singing is personal. And warming up is a dynamic, in-the-moment process. It should not be formulaic, but responsive to the needs of the singer on the day, and we never start in the same place twice in terms of how our body is, or where we are psychologically or emotionally. All models are wrong – the art is to find something within them that might prove useful.

In my early years as a teacher, a wise mentor told me that our goal as teachers should be to find ways of making ourselves redundant in our students’ lives as quickly as possible. I hope that this model goes some way to achieving that.

When are you going to post about runs, fast singing, coloratura, etc?

I think these are interesting topics, and would like to write about how I teach them – I’m just not sure when I’m going to find the time! In the meantime, here are some quick thoughts:

Hopefully, I shall find time to write more fully about all this!